Housing Poverty: Whose Land is it Anyway?

Posted on 19 Feb 2016 under Housing, News, Latest News

Richard Rawes, Chair of the Webb Memorial Trust, reflects on recent events at the Town and Country Planning Association, Institute of Economic Development and New Economics Foundation.

The Webb Memorial Trust has been supporting the TCPA recently on its excellent Planning4People initiative. This feeds into the current debate about the reduced role of planning in the context of major changes in the current Housing and Planning Bill. Some see this as part of a dismantling of the post war cross-party consensus on planning, as the key means of balancing social, economic and environmental considerations in the way we use our land.

Attending recent planning and economic development events at the TCPA and elsewhere has made me reflect on the impacts on poverty and inequality of the UK’s approach to land and property, particularly in relation to our current housing crisis. Here are a few thoughts.

Housing and generational inequality

Around half of the net wealth in the UK consists of land and property. While much recent work on poverty and inequality has focused on inequalities in income, inequalities in wealth are even starker, and the operation of the land and property market has a major bearing on this. This has a particular impact in maintaining inequality of opportunity over generations, particularly related to housing. Taxing wealth is a contentious area, as demonstrated by political debates and the recent raising of the threshold for inheritance tax.

The level of taxation in the UK on land and property is low. Unlike in the USA and many European countries, there is no capital gains tax on the rise in value when selling your main property, though the recent changes in stamp duty have now increased taxation levels on high value properties. In terms of an annual property tax, the council tax system is way past its sell-by date. Firstly, it is a highly regressive system, with marginal tax rates reducing significantly as property values rise. But more importantly, there is a maximum property value above which there is no increase in taxation. This upper limit was set at £320,000 when properties were last revalued in 1991; this is equivalent to around £1.15m now, based on average changes in UK property values. This means that, whether a house is valued at £1.2m, £5m, £10m or £50m, the same level of council tax is being levied.

The added-value of planning

The value of land is not a given. It is largely created by public infrastructure projects, such as public transport, roads, schools, parks and public services, together with a planning system which creates value through permission for specific uses. So every time there is a major public investment project which enhances land values, the private property owner gains, with little or no taxation on the enhanced value.

The pioneers who set up the post war New Towns, as for the earlier Garden Cities, understood this well. The New Towns were set up under financial models which ‘captured’ the rise in value from open land to commercial and residential uses and utilised this to fund community benefits, including the future maintenance of buildings, open spaces, etc. for future generations. This was integral to their success. These towns have been astonishingly successful, not just in terms of housing but also economic development. The top two investment locations for new businesses in England are Milton Keynes and Warrington – both New Towns designed by planners. So much for the myth of planning being the ‘enemy of enterprise’!

Whither affordable homes and local infrastructure?

Since 1947, when the landmark Town and Country Planning Act came into force, there had been a recognition that developers need to make a contribution towards the local infrastructure required by their development, such as roads, schools and open spaces, and to benefit those communities affected by the development. However, the new ‘permitted development’ regime allows the enormous rise in land values arising from the conversion of commercial to residential uses to be retained by the landowner or developer. This is being further extended under the Housing and Planning Bill to enable automatic permission for housing on ‘brownfield’ sites. This leaves the costs of those elements previously funded by the development – affordable housing, education, transport and leisure facilities, etc. – either to be lost or to be picked up by hard-pressed local authorities.

Additionally, there is no guarantee that the original intention, to enable more housing to be built, will be achieved as it may well be more beneficial for landowners to simply bank the land. Peter Bill, in Planning magazine, gives the example of one company that bought eight office blocks around London for £30m in 2013/4 to exploit the new rights. The offices have all now been sold, with permission for housing, for £56m. Not a single home has yet been built.

The government does not appear to be monitoring the hundreds of millions of pounds of financial losses to the public sector of ‘giving away’ the value of this change from commercial to residential use. In London alone, a London Councils report estimates that over 800,000 square metres of commercial space have been lost to date, in the process of which 1000 affordable housing units have been foregone which would have been negotiated under normal planning rules.

So, apart from the loss to the public purse, this change is in effect reducing the number of new affordable homes being built. Two other proposals in the Bill are likely to have a similar effect. Requiring housing associations to sell their properties through ‘right to buy’, with their losses made up by local councils having to sell off their more valuable council housing, will clearly reduce the number of affordable units available for those in need. However, a consequence of both this and a further requirement for them to reduce their rents by 1% per annum is forcing them to rethink their investment plans, plan ahead more conservatively and reduce the number of new homes that they will commit to building.

Private sector supply; the numbers don’t add up

Most commentators agree that there is a desperate shortage of affordable housing which, together with the low level of house building overall, is pushing up prices and making a major contribution to household poverty. It is clear that the switch in the 1980s, from government support for housebuilding to subsidies for home owners, has been a failure. Private sector supply is not achieving the numbers, ‘right to buy’ has reduced the affordable stock, prices have rocketed and housing benefit has therefore gone through the roof. The current government attempts to cap levels of housing benefit is tackling the problem from the wrong end and simply pushing more families into poverty.

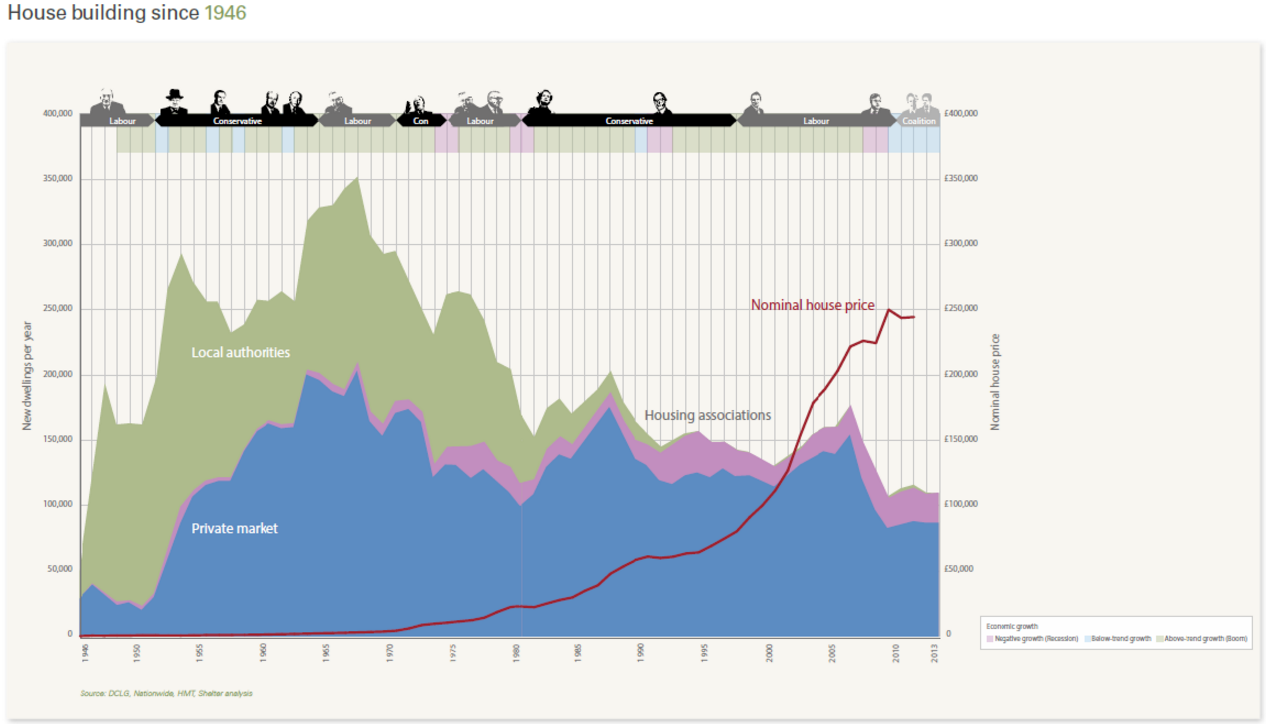

One of the many lessons that we appear to be ‘unlearning’ is that private sector development alone has never produced the housing numbers needed in the past and will not solve the problem now. With around 240,000 houses needed each year, the graph from Shelter below shows that the private sector has never achieved anywhere near that number since the war. Large numbers of new homes are only built when central or local government takes an active role.

Housing was built on a large scale in the 60s and 70s when local authorities were allowed to borrow – they could do so again if public sector debt were not seen as a more important economic measure than housing completions. Capital funding has reduced as a proportion of GDP from 7-8% in the 1960s to 1.5% now, the former figure reflecting the priority given to new public housing after the war.

If we are really to solve the double crisis of too few homes and unaffordability, we desperately need some of the courage, vision and foresight that all political parties shared after the Second World War.

Building the homes that we need

Firstly, local authorities should be given the financial powers that they need to invest in the future. This argument appears to have been accepted by the government for major transport schemes but not for housing. In support of this, a new Capital Economics report says that the Treasury could make a surplus over time by investing in new homes. All of this in my view points to local authorities being given the powers to borrow, taking advantage of low interest rates.

Public investment in new housing could create revenue streams for local councils to enable them to be more self-sufficient in future, as well as providing much needed social and private housing on their land, while retaining the freehold. It is councils who are at the sharp end of dealing with rising homelessness and this would give them the powers and responsibility to deal holistically with the issue. This must be a better long term proposition than simply ‘bringing public sector land to the market’ – or ’selling off the family silver’. This will have the added benefit of ensuring that housing, infrastructure and public realm issues are aligned, working closely with local communities.

But we will need more than this. Tackling the current shortfall will require a new generation of New Towns, together with carefully designed extensions to existing conurbations. And, if communities are to benefit, rather than just landowners, we need to learn the lessons of the past. Key to creating better places, with decent transport, environmental and cultural facilities, are the powers to acquire, own, manage, build on, dispose of and make decisions on land, with land assembly at existing use values. This is in stark contrast to developer-led regeneration and laissez-faire planning.

It is clear that we have the knowledge to address housing poverty and build the homes that we need, together with tried and tested systems that have worked well in the past. But the system is being unpicked and the lessons forgotten. To conclude with the words of Dr Hugh Ellis of the TCPA – ‘we are not a poor nation – but we are really badly organised’.

Note: This blog gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Webb Memorial Trust or APPG for Poverty

Comments